Between 1933 and 1945, Shanghai was a unique geopolitical anomaly, a divided city with multiple foreign-controlled concessions. Within this international metropolis, the German community comprising businessmen, diplomats, Nazi party officials, and military personnel – became a key focal point for the Third Reich’s overseas ambitions. The German Consulate, the Hitler Youth (Hitlerjugend), and the League of German Girls (Bund Deutscher Mädel, or BDM) played active roles in aligning the German diaspora with Nazi ideology. Meanwhile, Shanghai also became a crucial refuge for thousands of Jewish refugees escaping Nazi persecution. The coexistence of Nazi sympathizers and Jewish refugees, as well as the interplay between Germany’s political interests and those of its Axis partner Japan, created a highly complex and often paradoxical situation.

The Rise of Nazi Influence in Shanghai (1933-1937)

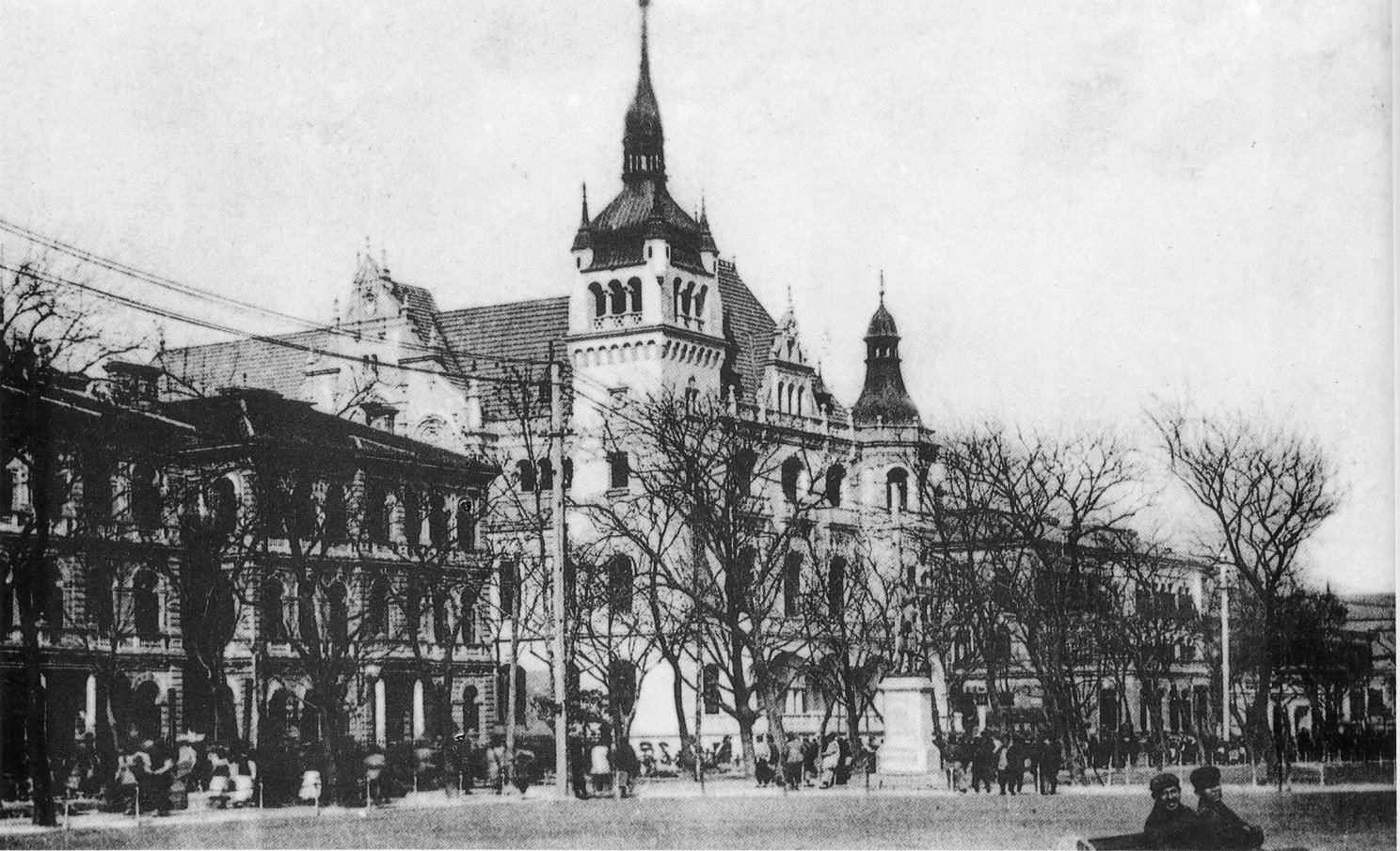

Shanghai’s German population, numbering around 1,500 in the early 1930s, was made up of diplomats, businessmen, missionaries, and adventurers who had settled in the city during previous decades. Many were employed by large German firms such as the shipping company Norddeutscher Lloyd and chemical giant IG Farben. A strong nationalist sentiment had always existed among this group, but with Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, German institutions in Shanghai quickly aligned themselves with the Nazi regime.

Under Consul-General Karl Ritter (1933-1936) and later Ernst Woermann, the German Consulate became the primary tool for spreading Nazi ideology among the expatriate community. The consulate funded pro-Nazi newspapers such as the Ostasiatischer Lloyd and closely monitored political dissidents. German schools in the city – including the Kaiser Wilhelm Schule – introduced Nazi curricula, incorporating racial theories and nationalist propaganda.

The Nazi Party’s Ortsgruppe (local group) in Shanghai was an extension of the NSDAP-AO (National Socialist German Workers’ Party – Foreign Organization). Led by figures such as Heinrich Dirksen and later Karl Friedrich Tiemann, it maintained strict ideological discipline within the community.

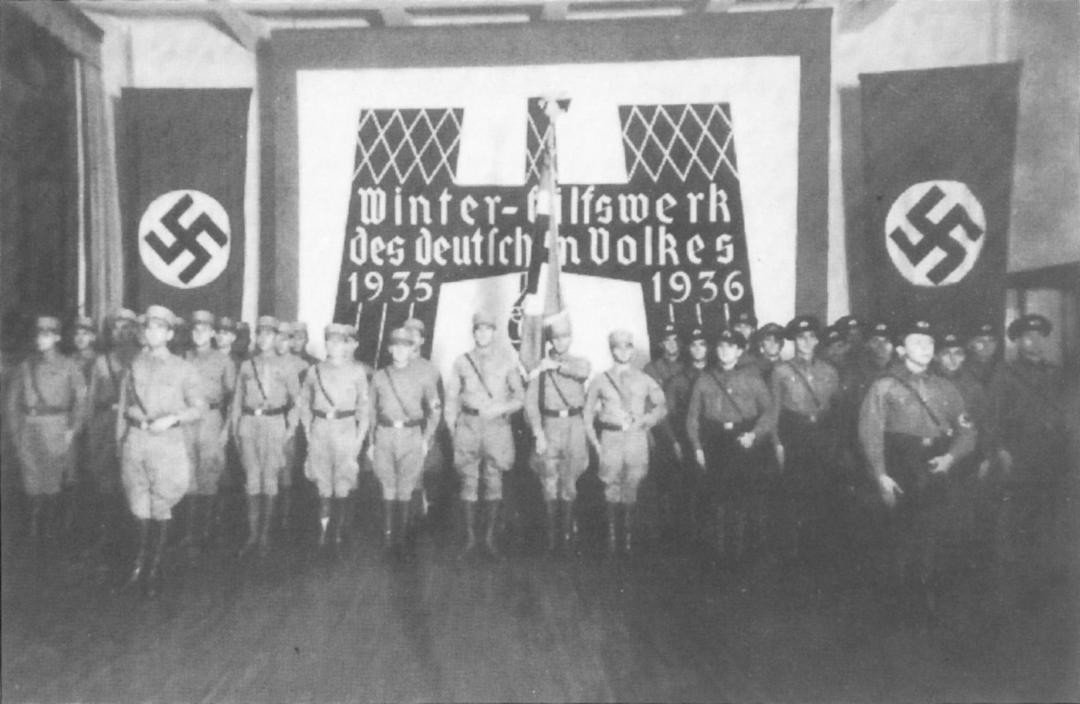

The Hitler Youth (Hitlerjugend) and the League of German Girls (BDM) played an important role in indoctrinating German children in Shanghai. Young boys underwent paramilitary training and ideological education, while BDM activities focused on traditional gender roles, emphasizing the virtues of Aryan motherhood. These groups often held rallies at the German Club Concordia, where swastikas and Nazi banners were displayed prominently.

Before the outbreak of war, German diplomats in Shanghai worked closely with their Italian counterparts, particularly after the Rome-Berlin Axis was formalized in 1936. The Italian Consul-General, Count Galeazzo Ciano (who would later become Mussolini’s Foreign Minister), maintained warm relations with the Germans. The Corriere di Shanghai, an Italian newspaper, frequently echoed Nazi viewpoints, fostering a shared fascist ideological space in the city.

At the same time, Germany was careful to maintain strong ties with Japan, which controlled much of Shanghai after the 1937 Battle of Shanghai. The relationship between Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan in Shanghai was pragmatic; both powers sought to curtail British and American influence, but their racial ideologies often clashed.

Nazi Shanghai During World War II (1937-1945)

Following the Japanese invasion of China in 1937, the geopolitical landscape of Shanghai changed significantly. The city became a battleground, with the International Settlement and French Concession remaining neutral zones while the Japanese occupied the rest. The German community, due to its Axis affiliation, enjoyed a privileged status under Japanese rule. Nazi diplomats and businessmen manoeuvered carefully, supporting Japan while ensuring that German economic and political interests remained intact.

By the late 1930s, the Gestapo had established a presence in Shanghai, working closely with Japanese intelligence agencies such as the Kempeitai. The Gestapo’s main objectives included monitoring German political dissidents (particularly communists and socialists), spying on British and American activities, and keeping an eye on Jewish refugees. Several German residents, including informants like Karl Helfrich, reported on anti-Nazi individuals to the authorities.

One of the most paradoxical aspects of Nazi influence in Shanghai was its uneasy coexistence with the city’s Jewish refugee population. Between 1938 and 1941, thousands of Jewish refugees, primarily from Germany and Austria, arrived in Shanghai seeking sanctuary from Nazi persecution. These Jews found refuge in the Hongkou district, which became known as the Shanghai Ghetto.

While Nazi authorities in Berlin pressured Japan to implement anti-Semitic policies, the Japanese were largely indifferent to Nazi racial ideology. Japanese authorities treated Shanghai’s Jewish population pragmatically, seeing them as potential economic assets rather than racial enemies. Despite German efforts to encourage stricter measures, Japan refused to enforce a “Final Solution” in Shanghai, frustrating Nazi officials.

Anecdotes of Nazi Activities and Internal Conflicts

- Karl Tiemann and the Battle for Nazi Leadership: In 1939, Karl Tiemann, the Nazi Party’s local leader in Shanghai, engaged in bitter conflicts with other German officials. His authoritarian style and corruption alienated many, leading to internal power struggles within the Nazi hierarchy. The Gestapo eventually intervened, replacing him with a more disciplined figure.

- The German School Incident: In 1941, a scandal erupted at the German school in Shanghai when a Jewish teacher, who had been employed before the Nazi takeover, was dismissed due to racial laws. Several German parents opposed the decision, arguing that their children’s education should take precedence over politics. The German Consulate, however, stood firm, reinforcing the Nazi racial doctrine.

- The Failed Plan to Deport Shanghai’s Jews: In 1942, Nazi diplomat Josef Meisinger – known as the “Butcher of Warsaw” – arrived in Shanghai, proposing a plan to exterminate the Jewish refugees by deporting them to a concentration camp on Chongming Island. However, the Japanese authorities refused to implement his plan, dismissing it as impractical.

The Fall of Nazi Shanghai (1945 and Aftermath)

As the war turned against Germany, the Nazi presence in Shanghai weakened. By 1945, the German Consulate was effectively powerless, and Nazi-affiliated businesses faced severe financial difficulties. After Germany’s surrender in May 1945, German citizens in Shanghai were classified as enemy aliens by the Allies. Many were arrested and interned, while others went into hiding.

Following Japan’s surrender in August 1945, Allied forces took control of Shanghai. Former Nazi officials, including Karl Tiemann, were interrogated. Some German expatriates who had collaborated closely with the Nazis were deported to Europe to face trials, while others remained in China, trying to erase their past.

The Nazi presence in Shanghai was a striking example of how Hitler’s ideology attempted to extend its reach far beyond Europe. The German community in Shanghai, deeply influenced by the Nazi Party, played an active role in promoting the Third Reich’s interests in Asia. Yet, the city’s unique status – controlled by multiple foreign powers, including a reluctant Japanese ally – meant that Nazi policies were not always implemented as intended. The paradox of a Nazi-aligned German community coexisting with Jewish refugees further highlighted the contradictions and limitations of Hitler’s racial empire. By 1945, with the collapse of the Third Reich, Nazi influence in Shanghai disappeared, leaving behind a complex and often forgotten chapter of World War II history.

SOURCES: