nota. This paper is an adaptation of an earlier French language article by the author published on The Souvenir Français Asie website on April 18, 2010

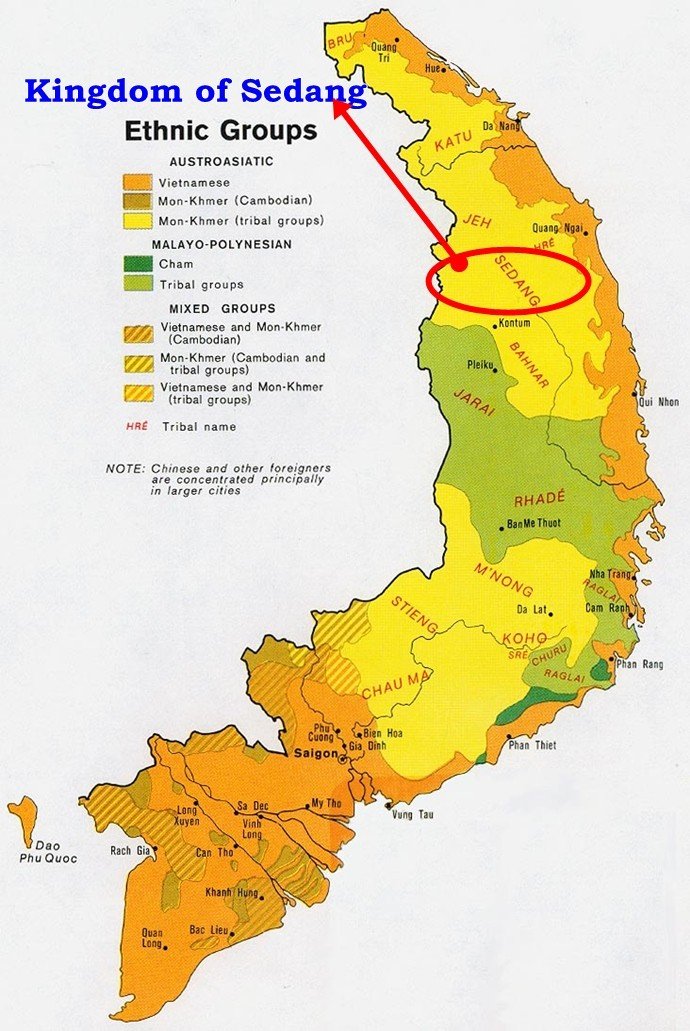

Throughout history, certain individuals have stood out not for their birthright or military conquests, but for their sheer audacity in seizing power where none existed. One such figure was Marie-Charles David de Mayréna, a French adventurer who, in the late 19th century, declared himself Marie I, King of the Sedang. His short-lived kingdom, established in 1888 in the remote Moï hinterland in modern-day Vietnam, coveted by the Siamese and that no one has yet conquered., was a bold experiment in personal monarchy, fueled by European imperial ambitions and indigenous political dynamics. Though ultimately doomed, his story remains one of the most extraordinary and theatrical episodes of colonial history.

Marie I’s kingdom was founded in the Central Highlands of present-day Vietnam, an isolated ‘grey area’ and rugged region inhabited by various indigenous groups. The Sedang people, an Austroasiatic ethnic group distinct from the Vietnamese majority, formed the core of his support. They lived alongside other highland tribes, including the Bahnar, Jarai, Mnong, and Rhade, who had long resisted control by the lowland Vietnamese rulers. At the time of Marie I’s rule, the estimated population of the Sedang Kingdom was between 100,000 and 120,000 people if we include the Bahnar, Jarai, M’nong and Rhade.

In April 1888, after persuading local tribal leaders that he could offer them protection and influence in the face of Vietnamese and French colonial expansion, Marie-Charles David de Mayréna declared himself King of Sedang. With his formal enthronement, he introduced a European-style monarchy, complete with a Constitution, bank notes and stamps, noble titles, military decorations, and national symbols. He envisioned a modern kingdom that would merge indigenous traditions with Western governance, placing himself at the center of this ambitious enterprise.

To establish his legitimacy, Marie I designed a national flag for the Sedang Kingdom. It featured a red star in a white cross, reflecting European influence and his claim of divine kingship. He also introduced a coat of arms.

In his effort to create a structured monarchy, he established various orders of knighthood and military decorations, modeled after European chivalric traditions. The Order of the Sedang Crown was the highest honor, awarded to those who contributed to the kingdom’s success. The Order of the Star of Marie I recognized military and civil merit, while the Order of the Royal Tiger was reserved for high-ranking chiefs and European supporters. These elaborate insignia were commissioned from European jewelers, reflecting his desire to elevate Sedang’s status in international diplomacy.

Governance and Military Organization

Marie I sought to build a functioning government by organizing a royal court similar to those of European monarchies. He distributed noble titles to both indigenous chiefs and his European supporters, creating a hierarchy that included the Grand Duke of Sedang, as well as various dukes, counts, and barons. His Royal Council of Ministers was composed of European advisors and local tribal leaders, though the effectiveness of this administration was questionable.

Military organization was another challenge. Marie I attempted to create a structured army by recruiting local warriors and organizing them into units modeled after European forces. However, he lacked sufficient weapons and logistical support, making his military ambitions largely symbolic. While he styled himself as a protector of the Sedang people, his kingdom remained vulnerable to external threats.

Diplomatic Efforts and Colonial Opposition

To secure the legitimacy of his rule, Marie I sought diplomatic recognition from European powers. His first and most logical approach was to the French government, hoping that they would support his rule as a client state under their expanding empire in Indochina. However, France saw him as a rogue adventurer whose actions complicated their colonial ambitions. When Paris refused to acknowledge his kingdom, he turned to other European nations, including the Netherlands and Germany, hoping to gain financial and military backing. He even appealed to Kaiser Wilhelm II, proposing that Sedang become a German protectorate. These efforts, however, proved fruitless.

By 1889, French authorities had grown increasingly hostile toward Marie I, viewing him as a direct challenge to their control over Indochina. They moved swiftly to undermine his influence and sought to remove him from the region. Realizing that his dream of ruling Sedang was unraveling, Marie I fled to Singapore and later to the Dutch-controlled island of Tioman (modern-day Malaysia), where he continued plotting his return.

Exile and Mysterious Death

Marie I’s exile was marked by continued but futile attempts to reclaim his throne. Isolated and without allies, he found himself increasingly desperate. In November 1890, he died under mysterious circumstances on Tioman. The exact cause of his death remains unknown, with conflicting reports suggesting natural causes, poisoning, or even suicide. Some speculated that French agents had orchestrated his death to prevent any further disruptions to their colonial administration in Indochina. With his passing, the Sedang Kingdom disappeared, fully absorbed into French Indochina, and his ambitions faded into history.

Legacy of Marie I and the Sedang Kingdom

Although his reign lasted barely two years, Marie I left behind a fascinating legacy. His coins, medals, and decorations remain rare collectibles, sought after by historians and numismatists as relics of his audacious experiment. His story is often compared to other European adventurers who attempted to establish personal empires in colonial territories, yet few came as close as he did to realizing their dreams. His tale serves as an example of how the colonial era allowed bold and eccentric individuals to carve out ephemeral kingdoms in the uncharted corners of the world.

Despite being largely forgotten outside academic circles, Marie I’s self-declared rule remains one of the most bizarre and captivating episodes of 19th-century colonial history. His dream of an independent Sedang kingdom was ultimately crushed by the realities of imperial politics, yet for a brief moment, he was a king in a land of his own making. His story is not just one of failure, but of remarkable ambition – an adventurer who dared to defy convention and crown himself a monarch in the heart of Southeast Asia.

SOURCES AND TO GO FURTHER

Hickey, Gerald Cannon. Kingdom In the Morning Mist: Mayréna In the Highlands of Vietnam, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 1988.

Marquet, Jean, “Un aventurier du XIXe siècle: Marie Ier, Roi des Sèdangs (1888-1890)”, Bulletin des Amis du Vieux Hué 14, nos. 1 and 2, 1927, pp. 1-133. Published by Impremierie d’Extrême-Orient, Hanoi.

Melville, Frederick John. Phantom Philately, Emile Bertrand, Lucerne, Switzerland, 1950 (first published in 1924), pp. 172-174.

Soulié, Maurice. Marie Ier, Roi des Sédangs, 1888-1890, Marpon et Cie, Paris, 1927.

Werlich, Robert. Orders and Decorations of All Nations, second edition, 1975, pphahaha. 149-151.

http://belleindochine.free.fr/Marie1erRoidesSedangs.htm